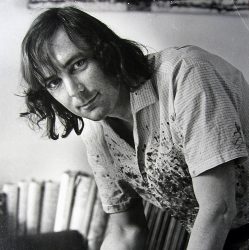

Marshall Baron – A Warm Memory

Written for his sister Merle.

OUR FIRST MEETING

My name is Roger Bell. I was born in Montreal, Canada in 1942. In June 1964, months before my 22nd birthday, I left for Europe on a freighter with the plan of hitch-hiking around the world for two years. I returned to Canada in June 1966.

One meets hundreds of people on a trip like this. The vast majority I met were friendly and hospitable. But it is rare to meet someone who is such a special person that you remember them warmly for close to a half century after. I was fortunate to meet such a person. His name was Marshall Baron and I write these lines in honour of him and for his sister Merle, who my wife found on the internet early in the year 2020.

After travelling through Europe, I met my girlfriend in Spain. I had fallen in love with her in our last year at Queen’s University, in Kingston. She was working in Ghana for CUSO (“The Canadian University Service Overseas”). We made our way down to Ghana through Morocco and hitching a ride on a British freighter from Casablanca.

After many wonderful months together in West Africa, I continued alone on my trip. I went through the Congo and Angola. Taking the Benguela Railroad back to the Congo, I then made my way down to the Zambia, with the help of an American who had a Cessna airplane since the border was closed because of mercenaries, and then to Southern Rhodesia.

It was there I met Marshall in late May 1965. I was standing on the road south from Bulawayo heading for South Africa. I had dropped my backpack to rest and was sitting by the roadside. I remember I was playing Bobby Dylan’s “Blowing in the Wind” on my harmonica when I saw the car coming. I stood up, stretched out my arm and it stopped.

“Where are you headed”

“South Africa”

“Jump in. that’s where I’m going! Is that a harmonica you have in your hand?”

Off we went. I smiled and nodded and played him the Dylan piece. He laughed, beamed a gigantic appreciative smile and I think said “Great”. This was my introduction to Marshall Baron, his generous hospitality and his friendly, laid-back personality.

We chatted vividly, though I remember him asking more questions than simply babbling on like some drivers did. Other drivers would also listen to what I had to say but would then use that to springboard onto long stories of their own. Marshall, however, was curious, but also open and appreciative to everything he heard. He listened well. His broad, almost Puck-like smile and gentle laugh made me feel welcome and happy. Neither his questions nor what he said was ever aggressive.

He explained he was going to a court just over the South African border to argue a case for someone accused of culpable homicide. Pro bono I think he said.

Arriving in the court town, Marshall asked me if I would like to stay the night and witness the court proceedings the next morning. He generously put me up where he was staying. Considering I normally slept in a truck or on a field, this was a huge and appreciated luxury. We had a wonderful dinner as well, chatting interestingly the whole time. He never talked about any of his achievements. We discussed ideas, philosophies and feelings. Marshall talked incredibly clearly and succinctly. He had a cadence when speaking. And a smile that seemed printed on his personality.

On my trip I kept notebooks, or a diary. And I add a few of those notes in this memoir.

CULPABLE HOMOCIDE

The hearing was a slow and tedious process. Every question and answer was followed by a two-minute pause for the magistrate to record it and the translator to explain it. Then the Magistrate would grunt and the hearing would proceed.

Marshall drily and professionally made his arguments. There were no theatrics.

There were three booths, one large, long table, one bench and a side room. The witnesses and the accused faced each other across the long table. The prosecutor and the defense attorney sat on the respective sides.

The doctor and then the wife described with relish and emotion the appearance of the beaten husband. Marshall made the point strongly that it was he who was the victim. “Yes, my worship” the wife called everyone.

“How often did he drink?” She was asked.

“On week-ends” she replied almost hopefully – strongly trying to reconstruct the past.

In the end, the accused was given a £20 fine and a six-month suspended sentence – with the condition that he would have no more assault charges against him.

Marshall had won. The victim’s violence when drinking had been established.

After his win, Marshall and I parted. Spending two days with someone like that left you with a contented feeling. His ability to read me and know I would enjoy the experience of the court was an ability I sensed that was a special skill. As was his empathy. He had shared many thoughts about his opinions of justice, his love of Africa, his love of music and painting – but all in a very low key way. I had talked about Canada, my dreams, the girlfriend I had left in Ghana and some poetry I was writing. I had now been over a year in Africa and shared his love of the sub-Saharan Africa.

We left with a warm good-bye and Marshall then said that I should contact him in Bulawayo when I returned North – which was my plan. He said it, quietly and not insistently, but in a way as if he wanted it to happen. Most every word Marshall said had import. He didn’t guild the lily. He wasn’t superficially loquacious.

A VISIT TO BULAWAYO

I then went to Cape Town and signed up with the Marine Diamond Corporation. I was almost broke and they paid extremely well. They flew me up to Luderitz in South West Africa then speed boated me down to the mouth of the Orange River where three huge dredging boats and five supply vessels worked about a mile of the desert coast. They dredged for diamonds. I worked as a dredging operator for 12 hours a day. They X-Ray you when you left to return to Cape Town to ensure you hadn’t swallowed any diamonds.

After a few more eventful months touring South Africa I headed back north. My aim was to see other East African countries and Bulawayo was a natural stop. I arrived in late August 1965. With some trepidation, I got in touch with Marshall. One never really knows if someone’s “Come and see me” is genuine.

No need to worry. “19 Oxford Road”, he said. “No, forget it I’ll be over in ten minutes to pick you up.” It was as if we were old friends. He insisted I stay several days.

These were special days. We talked as if we’d known each other for years. Marshall’s curiosity, empathy and superb listening ability made that easy and enjoyable. We played chess and talked even while he was painting, listening to music the whole day. I met his mother and father, both of whom were engaging, helpful and welcoming, but not at all fussy and constantly at your heels.

A MORNING WITH MARSHALL

The sun rays lingered in the windows. The breeze billowed out some curtains and then rummaged as breezes do through the shambles of papers, paint cans, blankets and books next to the window wall where the morning sun hesitated and then halted a few feet into the room giving up the battle to the quiet, dark interior of the studio and the sound of music. The deep and masculine movement of Bartok music played – disturbing and demanding courage. Marshall painted stroke after stroke, blue coating the canvas in abstract brush movements, joined to the power of the music, the scene suffocating all possibility of individuality for the moment.

Later I asked the question, “When I get back home and want to start a collection of good music, what are some suggestions you might have – similar to what we were listening to? I liked that.”

Marshall quickly prepared a list. He wrote the following titles:

1. The Miraculous Mandarin Suite, Opus 19. Bartok performed by George Solti.

2. The Don Quixote Dances, with Roberto Gerhard.

3. Curt Nielsen, Opus 50.

4. And then added were: The 10th Concerto in B Flat Major, and the 15th String Quartet in A Minor, Opus 132 – both by Beethoven.

Later, during a chess game, there were discussions about music. I wanted to understand music. For example, one discussion went: “… a concerto, you should know, is a concerto Grosso. A Ripieno is more a concerto. The overall movements are similar to a Sonata. In a church, you play a Sonata da Chiesa with abstract movements. But in a ‘chamber’, you play a Sonata da Camera with dance movements,” Marshall explained. Patiently, with joy – never pedantically.

Going further, Marshall would explain that with the Cadenza, there was more stress on virtuoso, while the idea of contrasting passages is the essence of the concerto. The summary of that discussion, then, made a point about the Sonata, such as those typically by Hayden, Mozart and Beethoven. Namely, when the instrument suite gave place to the sonata or symphony plan, the concerto Grosso was supplanted by the classical concerto!

Marshall was quite unbelievable. I would take five or six records without his knowledge from his huge collection while he was painting. “Listen,” I would call out. He was in the next room. I would place the needle somewhere on each record and within only a few thoughtful seconds, the call would come “The Brandenburg …. Bach… #5 … 1st movement … allegro,” and he was always right.

Recording this discussion has not been easy. Remembering will be impossible. I resolved to enjoy music, but not to try ‘understand’ it. With Beethoven in the background and the chess game heroically unravelling below, it seemed like the scene the heart demanded.

We also toured. Marshall loved the Rhodesian countryside.

THE MATOPOS

50 times 30 miles of bare granite and green valleys just to the east of Bulawayo. Marshall would go running here. Here I stood looking over the vast expanse at a place aptly called ‘View of the World’. Further on, the Zimbabwe National Park. It was as if Marshall was a kid showing me a loved birthday present.

THE KYLE DAM

203 feet high, 1,020 feet wide. Granite hills and deep ravines slid with abrupt swiftness into the placid waters and sylvan setting of Lake Kyle, whose thirty-five square miles of water press on the simple and majestic success of the Kyle Dam and then pour in a blossom of spurting water into the river gorge that takes it down to the sugar farming estates 2,000 feet below the escarpment to the East, in the booming low veldt.

THE ZIMBABWE NATIONAL PARK

Here there is a large black oval National Park stamp, the date is clearly printed. It is the 30th of August 1965.

Close by, I we come to Valhalla, a native burying place. Matabele’s king Mzilikazi led his people out of Zululand here in 1838. Rhodes made his black oxen sacrifice nor far away. Here were the ‘Ruined Cities of Mashonaland’ found in 1890. By 1902, a curator was appointed to undertake making it a tourist site! That was early tourism. It was, after all, the most exciting discovery ever made by archaeologists in Southern Africa. The vegetation around the ruins is very luxuriant, since Zimbabwe is higher than the surrounding countryside and has more rainfall. The acropolis of the ruins is shrouded in frequent mists which rush in and out of the cramped doorways, and up and down the passageways of earlier civilizations. Now one could sit in “The Ruins Cafe” and enjoy a cola while taking it all in.

What was the background? Dominating the wild bush country of the south east of Rhodesia’s oldest town, Fort Victoria, lie the massive ruins of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe means ‘Houses of Stone’. The ruins are redolent of a mysterious past – a past of pagan ceremony, of the lost empire of Monomotopa and of the hinterlands gold trade, now dead, that was then carried on with the Arabic ports on the Indian Ocean.

Zimbabwe is the most impressive of the ruins. It is at least a thousand years old. It lies between the Sabi and the Limpopo Rivers and west of Bulow. It was robbed by early treasure seekers. The temple and the fortress of Mambo of Monomatopa was thought to be the sanctuary center of an empire sprawled around all of South Central Africa. The Mambo was a priest King and Zimbabwe was the center of a rain-making cult of which he, the Mambo, was the embodiment.

The Great Wall was thirty-two feet high at the Acropolis and sixteen feet thick at the widest point. The space enclosed was 350 feet across. The conical tower was the center of an elliptical temple. Within its defenses, a complex of walls, enclosures and platforms were all cleverly integrated with the granite boulders of the summit. Camouflage. Quarrying was then done by lighting fire on huge granite patches to crack them by the heat. To do this, vast areas were depleted of trees. Sledges were then used, like sleighs, to pull the rocks to the city under construction. This is now all next to thousands of acres of national parks where game, bird and natural fauna and excellent fishing abound. It is set in the pastel countryside of Msasa trees – the strange and unique Zimbabwean trees that come out in Canadian Fall colours before they bloom. 300 yards away are rest huts.

Marshall said he had been in awe of this place for many years. He presented it to me almost as a gift.

A diary poem: I wrote this a few days later from my notes, in commemoration of our visit. It was Marshall and I who sipped the tea mentioned.

CIVILIZATION

In granite green valleys and

with a view of the world,

they gathered

to build a civilization,

and here,

at Zimbabwe,

to bury chiefs

that constructed it.

Their bodies dried over fires

while maggots and body fluid were collected

for later religious uses

while meat was burnt

to disguise the odor

Of the decaying corpse.

The dried body,

hide-wrapped

burial hut rested

was protected by special guard.

This was all just below us here

where we now sip tea

and complain of the flies

that are his direct descendants.

Only with the long passing

Diary Note

of that Civilization

did we admit

that it was one.

AUDREY, OF THE PETERHOUSE MUSIC CAMP

(I had traveled here with Marshall who both played and occasionally taught at the camp. You felt it was a special place for him. You could tell he felt at home here.)

There were seventy youngsters at the Peterhouse Music Camp and among them, Audrey, with short black hair and a simple face saved by soft silky eyes of light blue green. People whose eyes mix colours like these either have a washed-out-looking face or, if lucky, instead look incredibly soft and vulnerable and caressable. Audrey was like that.

The thought of us together purified me and when I walked with her. I felt guilty and afraid as if I had stolen something precious from a church and would soon be found out and stoned. But it seemed that the pain of staying away from her was equal to the pain of the stoning and so we often walked together, embarrassed at being alone, but with a solitude that those of our age do not usually have. She was seventeen. She had something to suggest the yielding tenderness that the susceptible find so alluring.

These were wonderful days, relaxing and being laid back. It was the osmosis of Marshall’s personality to relax you like that, I think.

I then left to visit several other East African countries before booking a three deck below passage to Bombay, from Mombasa, sleeping in bunks three high with hundreds of poor Indians returning home.

I arrived home in Montreal in June 1966. I shaved off my beard and found a job with IBM selling typewriters and other office products.

Between then and the mid-1970’s Marshall visited me 4-5 times in Montreal, Ottawa and also I think Toronto. The first visit was unexpected but then the others followed, almost each year. We would tour the sites of the cities, spend hours chatting, play chess, walk up Montreal Mountain, and lazily enjoy our time together. It was if we were still in Africa in the sense that Marshall’s personality and behavior was his typical combination of calmness and animation of ideas always punctuated with humorous remarks and broad smiles.

On returning from my trip, I initially lived with my mother while looking for an apartment. On his first visit Marshall stayed with us in Montreal. Mother loved him. He quietly charmed her with his stories of Africa, complemented her cooking. She talked of him often over the next thirty years until she died. She was heartbroken when I told her that his mother had phoned me of his early death. We had a piano which he played.

All Marshall’s visits were enjoyable. He would only stay three-four days. We returned to our long, creative and rambling discussions, played chess and listened to lots of music either on the radio or from my meager collection. It was very easy to be with Marshall. He was never angry. He never boasted or even really talked about his achievements. In fact, it was not until 2020 when I was introduced to the website created by his sister Merle and her grandson Nadav that I learned of the profound praise he had received for his countless activities, achievements, writings, paintings and highly talented journal criticism He simply didn’t talk about or boast about all that. It was if he had been transplanted in another world and he only wanted to explore and enjoy it, like a child growing up. He never had his life swinging like a gaudy flag on a car antenna.

Big Personal Changes and the Mysterious Ludwig Story

Sometime around 1975-6 was the last time I saw Marshall. Soon thereafter I got a message from Canadian Customs that a large crate had arrived for me at Montreal airport. It was huge. 6 feet by four feet probably. I was mystified. When I picked it up, it said the sender was Marshal Baron. It was a present. There was no explanation letter … just a scribbled note saying something like “Dear Roger, This is Ludwig and he’s for you.”

The Story of Ludwig

It took an hour to gingerly unpack. It was one of Marshall’s huge abstract paintings. It took your breath away. My mother laughed gleefully when she saw it. However, it was so large and there were so many paintings in her house that we had nowhere to hang it.

Sadly, then, it went down to our basement, it stayed there for twenty years, looked at only occasionally, though with wonder.

In those ensuing twenty plus years I went to Harvard for an MBA, married a lady who had escaped Czechoslovakia with her family to avoid prosecution, joined the consulting Firm McKinsey in Germany and spent those years working there and Brazil, founding a practice for the Firm.

I returned to Canada in 1997 just months before my mother died and separated then amicably divorced a few years later.

Luckily, I met my current wife in 2000 and also took over the house my mother had lived in. She had been there for close to sixty years. So we embarked on several major renovation projects – among them building a huge deck that surrounded the back of the house and created French doors to open onto it.

When we finally got to the basement in a cleaning out frenzy, who did we meet? Ludwig, of course!

But there were now even more paintings in the house – my own and my mother’s. The same quandary. What should we do?

That’s when my wife came up with a stroke of genius – which could also, however, be considered a sacrilege. After twenty years we have decided it has been genius not sacrilege. We decided to hang Ludwig on one of our huge brick walls on the deck.

He has been there for twenty years now, in rain and sunshine and the winter snow. My wife carefully preserves Ludwig every year with various protective applications that bring out the colours. He is still looking fine!

And here’s the genius. Ludwig has been seen, admired and puzzled upon not only daily by us but by hundreds of visitors over the last twenty years. From May until October we sit out on the deck almost daily for cocktails, nibbles and dinners or just chats and we talk with Ludwig. And we know we’re talking with Marshall. He is an intimate part of the family. And all the guests, happily puzzling to find their special figures and meaning in Ludwig, hear warm and loving stories about the saga of Marshall Baron.

I had felt desolate when I had heard from his mother in 1977 that he had died. Now with him outside on our deck I feel he has been brought back to life. Fortunately, in 2000 I did not know of his major painting achievements. Had I known, perhaps we would not have brought him into the outside world. But in retrospect, it has been a happy decision. Ithink it’s more comfortable for Marshall to be outside than cooped in some dark inside corner.

Some random retrospective thoughts

I talked often of Marshall’s peacefulness and calmness. But I believe there must also have been a rage there. His painting and his music had rage in them. Both are highly emotional endeavors. There was a counter-authoritarianism and a dissatisfaction with the views of white Africans. Yet I believe he used the painting and music to control them, to subdue them, to understand them.

His love of Africa was obvious. Yet there was as if a split in his personality because in Canada and the U.S. new petals came out in his flower. As true to his personality as he always was, there was a different sense of peace, or freedom. I had experienced a lot of subtle and not so subtle racist talk when I was in Africa. But Marshall lived in it. I believe it hurt his sense of decency and loyalty. Furthermore, both Zambia and Southern Rhodesia were in tumultuous times, in the middle of a huge political chaos and often not a small amount of militarized revolt and danger during Marshall’s last twenty years. He never talked about it or complained – at least to me. And that was I think a very mature personality trait. And of course, Canada really had none of those issues. You sensed his release. But you also sensed the significant stress there must have been between thinking of moving to North America and yet abandoning a country and family he loved. You also sensed another stress, namely that he probably wanted and needed a partner but was unable to resolve the issues that would help him commit to one.

Marshall’s love of family was clear, yet I don’t remember him talking a lot about his parents and sisters. Nevertheless, it might be my fading old memory. I found addresses in my notes that suggest he had explained some background, and perhaps thought I might visit his sisters. There was the address for Beverly Baron in the Woman’s Residence of Wits University and then for sister Merle Gutmann at 22 Aluf David, Ramat Chen, Tel Aviv 34926! Furthermore, I had Marshall’s address as 7 Lawley Road, so my use of the Oxford address might have been a mistake, being a later move.

Although, as said before, there was a wonderful peacefulness and calmness about him, Marshall did not suffer fools gladly. Nor for that mater did he falsely compliment. In reading his music critiques in 2020 I am reminded of this: I was amazed to see how honest and direct, even cutting he was in his criticism – yet all the while remaining constructive and highly respectful of those with talent.

Jewishness: I was struck by the amount of time and energy the Baron family put into Jewish/Israeli causes. Marshall never talked about religion. We were together on many Fridays, but there was never a discussion of a Shabbat meal. I could quite easily have never thought he was, in fact, Jewish. Considering his family’s thoughts and actions, this puzzles me a little.

Marshall was, in some senses, a prodigy – musically, in his shrewd critical abilities and in his rule breaking abstract art. But for me and my memories, it was the humanity he represented that was prodigious. Most of us have had a lot of acquaintances and even friends. But for how many of them can you easily pull up a picture of one in your mind? For how many of them would just love to have another few minutes of their time? Marshall was one of those people for me. I miss him.

I hope this page and examples show that to be true.

July, 2020nn