Published by Kerber in Germany, is a beautiful and fascinating book on Zim art and artists, and is well worth buying. The chapter, “BRIDGING THE CONTEMPORARY” by Zvikomborero Mandangu features Marshall’s art as well – “Baron of Bulawayo” – and it is a very complimentary and highly enlightening text on Marshall’s contribution to Zim art, also featuring three of his paintings. The book can be purchased from Kerber, www.kerberverlag.com and the book is ISBN 978-3-86678-937-1. Thank you Zvikomborero Mandangu for your thoughtful analysis of Marshall’s art, and thank you to the Editor Ignatius Mabasa for an outstanding book, to the five contributors/writers Doreen Sibanda, Raphael Chikukwa, Farai Chabata, Tashinga Matindkike-Gondo and Zvikomborero Mandangu, and to the Designers Polina Bazir and Kerber Verlag.

You can buy the book here.

An excerpt from the chapter “BRIDGING THE CONTEMPORARY” by Zvikomborero Mandangu, published in the book “Insights on Art in Zimbabwe MAWONERO / UMBONO” published by KERBER, Germany, 2016

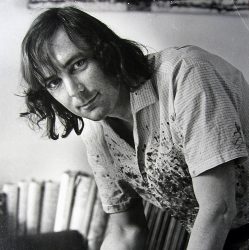

BARON OF BULAWAYO

After the fall of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in 1963, art was in the doldrums. A system that did not support McEwen’s arts initiatives had come to the fore by 1964. The race relations that had been established through art and paraded internationally were in a critical condition, aggravated by the Unilateral Declaration of Independence and the sanctions that were imposed on Southern Rhodesia.

McEwen’s work as Director of the Rhodes National Gallery became increasingly difficult, and his focus shifted towards individual artists who were creating works of art that resonated with social and political events. Marshall Baron was a lawyer by training who had won a scholarship to study art in the United States. His influences included Abstract Expressionism, and his work acquired expressive and emotional features that were derived from deconstructing conventional art forms, as in his painting Design for Communication.

The non-configuration of Design for Communication means that its capacity for expression is based on colour alone. The superimposition of warm and cool tones suggests the interaction between different parts. The fields of colour contain different types of strokes, so the texture varies. The chalky border serves as a field that contrasts and blends with the rest of the work. Baron was shifting away from the modernity that McEwen was marketing, notwithstanding the fact that his work was heavily influenced by Modern Zimbabwean Stone Sculpture, hence a continuous mimicry of stone-like forms in his paintings.

When compared with a painting by Stephen Williams, who was Baron’s prote̒ge̒, resemblances in style and abstraction of form can be observed. The landscape moves ponderously, with the dominant warm colours and hints of cool brush-strokes and gold precipitation falling on a neutral, dark horizon. The ochre foreground is similar to Baron’s usage in Tropic Threshold. Both works feature heavily expressive landscapes, which, in addition to their powerful hues, delineate the landscape they represent, namely a volcanic eruption.

Baron placed art in a context, which ensured that the content of his work was personal and unrestrained, to the extent that most of it was highly critical of the Rhodesian Front government of the day*. The difference between McEwen and Baron may perhaps be described as follows: McEwen used the community of artists around him as labourers to construct the pyramid that is now his legacy, compared with Baron’s scarred and deeply solitary way of addressing the flaws of a society suffering the evils of war and economic sanctions. While the former sought to gain profit and credit as an innovator, to appeal to the buyers of Modern Art, the other exposed government’s flaws from the wilderness, to the fury of a broken system. Viewed in this light, Baron inspired his contemporaries and a crop of younger artists such as Williams and Jogee, which set artists moving towards an emotive engagement with society.

Marshall Baron thus provided the emotion for the Contemporary art scene through his artworks. The form they assumed fitted into the historical context that underpinned the sculptural skills which McEwen found among local black artists. Baron’s paintings seem to have set a precedent by converting the Zimbabwe Bird, a national emblem, into a painting. In the 1970’s, Baron defined art as a vehicle for freedom which makes the distinction between pre-colonial and post-colonial artists easier to explain.

THE ARTIST IN PRE AND POST-INDEPENDENT ZIMBABWE

During the Unilateral Declaration of Independence era Rhodesia was subject to United Nations Sanctions which greatly affected the marketability of art. In 1966, a guerrilla war was fought by the forces of ZANU and ZAPU and for the next decade, civilians were recruited into the Rhodesian Defence Forces.

Rashid Jogee is a figure who stands at the centre of this battle of ideologies; black against white, capitalist against Marxist, and pacifist against imperialist. As an exponent of works by his mentors Marshall Baron, Paul Goodwin and Stephen Williams, Jogee found himself caught up in a racial war, with no affiliation to either side. Furthermore, he was conscripted into the Medical Corps by the Smith regime while teaching at the Mizilikazi Arts and Crafts Centre in Bulawayo. …….

Following the philosophy and liberal leanings of his role model, Baron, Jogee combined Eastern philosophy with Zimbabwean Stone Sculpture, just as his mentor had combined the same sculpture with Western philosophy. Jogee chose to incorporate elements of Stone Sculpture into his paintings as he considered it brilliant, and because it showed no Western influence. …….

The War of Liberation was an upheaval for many artists, who were living in the rural areas; a story that defines the social and economic impact on the artist in the run up to Independence is Brighton Sango’s transition from the war-torn north of Rhodesia (formerly Southern Rhodesia) to the city did not help him achieve his work. Baron, Jogee and Sango were foot-soldiers in the same artistic struggle.

It could be argued that the politics, social and cultural frameworks of the Smith regime had opened their eyes in a traumatic way. Their artworks were to become brutally honest and definitive, conveying messages that were reflected by the rifts between men. One could see how Sango, like Baron and Jogee, was an artist affected by war. A war that stopped him from being the man he truly was. A war that stopped him from being an artist. …….

However he developed his complex form, it paved the way for the ingenuity of an ever-growing Contemporary art scene. In particular, Sango’s Cubic style provided the breakthrough to sculpture that was tantamount to the contribution that Baron’s abstraction made to painting. ……..

CONCLUSION

Contemporary art in Zimbabwe can arguably be said to have started at the point where every aspect of Modernity was abandoned by one artist who sought to break with tradition. If Modern art merged with tradition through McEwen’s atelier approach at the Workshop school, then Baron arguably established the point at which the Contemporary art movement began in earnest. This shift was driven by his introduction of Abstract Expressionism to what was then Rhodesia.

Baron’s interpretation of the sculpture movement from ancient times established a well-versed account of tradition meeting Modernity. Williams, Goodwin and Jogee’s adaptations of their mentor’s philosophy was bolstered by the rise of Contemporary art.

The works of Marshall Baron sent shockwaves through the Modern Art scene in Zimbabwe, triggering the Contemporary art scene. ……..

The focus on the manifestations of the Contemporary art movement was now due to the fact that aesthetics were not the key means of evaluating art, as that meant succumbing to Modernity. The ability to express the occurrences that were affecting society and the artist in terms of colour and form became a central them; Jogee, Bickle, Gutsa, Williams and many other artists broke with tradition to discuss issues that were more personal than just painting landscapes and conventional portraits.

Framing the Contemporary was a shift that merged the traditional with the expressive. Painting and sculpture in Zimbabwe became a vehicle for expressing meaning, and a unifying factor for society. From Baron to the present day, art has served as a time capsule which offers a window to the spirit of different eras. The passionate metaphysical, expressive style which may be assigned to the period between 1976 to 1978 marks the birth of the Zimbabwean Contemporary art in a country that identifies itself with an artwork that is its national symbol; the Great Zimbabwe Bird.

*Williams, S. Cyril Rogers, ed. The Art of Western Zimbabwe in Southern African Art. National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Harare, 1992